The photovoltaics industry in Australia has recently been subject to two notably destabilising policy issues: on the federal level, falling REC prices, and on the NSW state level, the axing of the Solar Bonus Feed-in Tariff scheme. On the whole, the Australian solar power industry is booming like it never has before, thanks in big part to the federal Enhanced Renewable Energy Target‘s Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) program, which in effect provides up-front discounts for every expected kiloWatt-hour that a solar power system is expected to produce over the course of its lifetime (well, 15 years), based on system capacity and sunniness of its location. This scheme, coupled with state-by-state feed-in tariffs, has lead to the unprecedented uptake of residential solar power installations across the nation. But as has been pointed out, observed and felt in Australia, the start-stop nature of these programs can also result in volatility and instability in the markets.

Australian solar power policy: RECs and FiTs

The goal of good solar power policy (and renewable energy policy in general) is to promote sustainable energy production that does not harm the environment or deplete finite resources, while at the same time protecting against market distortions that will inhibit the long-term viability of the policy and the solar power/renewable energy industry. In essence, the purpose is to avoid (or at least mitigate the effects of) the boom-bust cycle as much as possible. What aspects of the federal REC program and the NSW feed-in tariff have resulted in the turmoil that we are currently seeing?

We have written in the Solar Choice blog about the REC multiplier, which, although a boon to those who have installed systems at significantly discounted prices, has resulted in the creation of ‘phantom RECs‘–RECs that do not represent kiloWatt hours of actual produced energy. These phantoms are accused of having deflated the average REC price (from over $40 previously to a current price of less than $30 as of this writing), making the up-front cost of a solar power installation significantly less affordable than it was when REC prices were higher. Another directly related source of uneasiness in the solar power industry is the fact that the REC multiplier is set to reduce from 1 July 2011, and no one is quite sure what this will entail. One theory is that, because it will result in a reduction in the number of available RECs, it may drive up demand for them and therefore increase their price, making installations more affordable. On the other hand, even with a higher price, there will be fewer RECs allocated for each system.

Meanwhile, in NSW the state government has decided to suspend the state Solar Bonus Feed-in Tariff scheme, which it accuses of having caused a price ‘blowout’, costing much more than initially anticipated and supposedly contributing to the rising cost of electricity in the state. The government has announced that it intends to take pressure off electricity prices by allocating money in the state budget to pay for the feed-in tariff scheme, resulting in a deficit where there should have been a surplus. What this means, essentially, is that instead of electricity consumers shouldering the dispersed costs of electricity through a burden placed on electricity generators via the purchase obligations of a feed-in tariff, as the nation (and the state) moves in the direction of greater reliance on renewable energy, the government is shouldering the price by tapping into tax revenues. Which is a better mechanism? In light of the ultimate goal of energy efficiency and decreased reliance on fossil fuels, if electricity prices do not rise and consumers do not strive for greater efficiency, it would seem that the policy is not doing its job. (Nevertheless, this policy should accomplish this goal in a way that is not erratic, disruptive, or unfair to those with lower incomes.)

Renewable Energy Certificates + Feed-in Tariff = Performance based REC?

It seems unlikely that the federal REC and state FiT programs will ever be harmonised with one another, although as it stands they do complement each other well and have been making solar power a viable and affordable choice for the average citizen. One possible policy tool that merges the two schemes in such a way is called a performance-based REC. This is the kind of system that is in effect in the USA state of New Jersey, where solar power has seen significant growth in recent years.

With the solar power industry looking to the government to provide some kind of stability in the markets, performance-based RECs offer another alternative. A performance-based REC system is one in which REC creation is ongoing and based on the real output of the system that generates the electricity that they are credited to, and in which government intervention in the market would not be required to the same degree. Ideally, this would allow REC prices to self-regulate without government micromanagement of the details, reducing administration costs and red tape. Performance-based RECs, the measurement of whose productivity is ongoing and intermittent, could potentially offer an incentive that better and more honestly benefits small-scale power producers, the solar industry, and the environment.

Under the current scheme Australian RECs are issued up-front with a set ‘deeming period’ of 15 years. Based on the location and peak capacity of the system under consideration, a greater or smaller number of RECs is issued. The actual productivity of the system is never fact-checked: as long as the system is wired properly at the time of installation–even if it is sitting under a tree–that system will be issued the same number of RECs as a system of the same capacity in the same location. Compare this to a feed-in tariff (FiT) policy, under which a small-scale grid-connected solar power producer is paid for each kiloWatt-hour of electricity fed into the grid.

RECs are a type of renewable energy currency, and therefore have fluctuating market value, and the REC system has been established with the end goal of achieving an active market for renewable energy that ultimately benefits the environment. The REC system has done amazing things to promote and spread the use of solar power, and has moved Australia along in leaps and bounds on its way to fulfilling its potential as a solar-powered nation. However, not measuring the actual productivity of the system, RECs are not effectively fulfilling their intended purpose under the current scheme–no matter how well your system is performing, you do not stand to benefit proportionate to that performance. If promoting solar power and encouraging efficient energy use in is the main goal, RECs are performing their job less than optimally.

Solar power: how performance-based RECs work

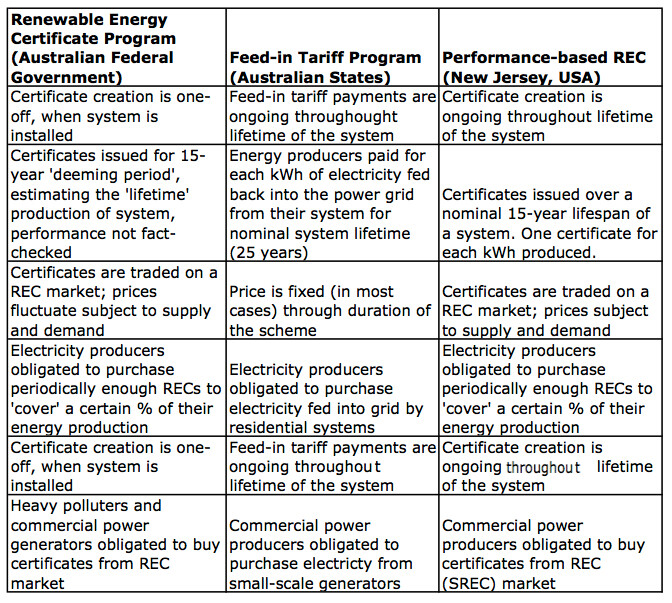

A performance-based REC system functions as something of a hybrid model of a Renewable Energy Certificate scheme and a Feed-in Tariff. The differences between the three systems are summarised in the table below.

Some key points to note:

-Performance-based RECs offer no up-front rebate, but do potentially offer better revenues (compared to conventional RECs) over the long-run

-With performance-based RECs, the price of certificates still fluctuates, but without the same degree of volatility.

-Installers are less susceptible to upturns and downturns in the market, because customers do not rely on the up-front discount that Australian RECs effectively provide.

-Residential solar electricity producers receive varying returns based on REC market rates, and may accumulate RECs, waiting to sell them until the price is favourable. The up-front discount that Australian RECs currently provide is instead distributed across the life of the system.

Whether performance-based RECS are appropriate for Australia cannot be said, and this policy tool is just one alternative of many to the current REC scheme, but there are a number of benefits, as described above. It is also worth noting that, despite all the issues that have recently arisen with Australia’s current REC scheme, it is still a useful and effective scheme that has enabled Australia to take great strides forward on its path toward 20% renewable energy by 2020. The solar power industry and its customers still stand to benefit significantly from the current REC program.

- Solar Power Wagga Wagga, NSW – Compare outputs, returns and installers - 13 March, 2025

- Monocrystalline vs Polycrystalline Solar Panels: Busting Myths - 11 November, 2024

- Solar Hot Water System: Everything You Need to Know - 27 February, 2024